INTRODUCTION:

In a previous report I had mentioned that I would be searching for remnants of the Hilliard Flume and Beartown. There might be a few of you who aren’t familiar with what we are dealing with, so let me explain.

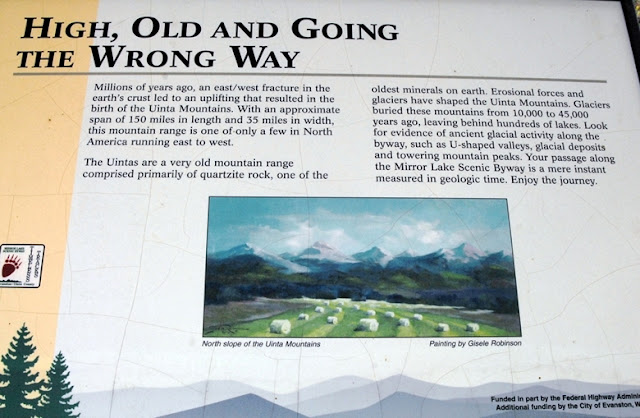

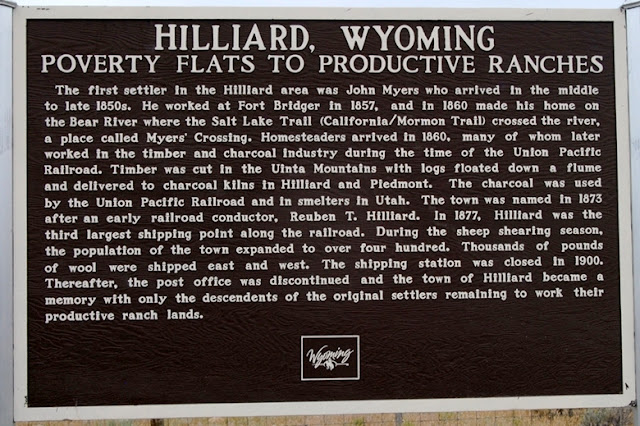

We are dealing with a group of tough guys I have called “unsung American heroes.” They are called “tie hackers,” or “tie hacks.” They were mostly Irish immigrant lumbermen who in 1867 were sent into the North Slope of the Uinta Mountains, and other areas, like the Wind Rivers, to make railroad ties for the Transcontinental Railroad. They incredibly worked 12 months a year in the most adverse conditions imaginable eventually producing millions of ties without which there would have not been a Transcontinental Railroad.

One of the first communities established by them in 1867 was Gilmer, or Beartown in Southern Wyoming.

Our search will take us to that area to pinpoint its location and find some remnant, maybe even some evidence of what caused it to become known as “The liveliest city, if not the wickedest in America,” where “the bloodiest battle between whites in the history of Wyoming,” took place. After our search for Beartown we will search for the Howe Feeder Flume, and then the tie hacker related ghost towns of Hilliard and Piedmont.

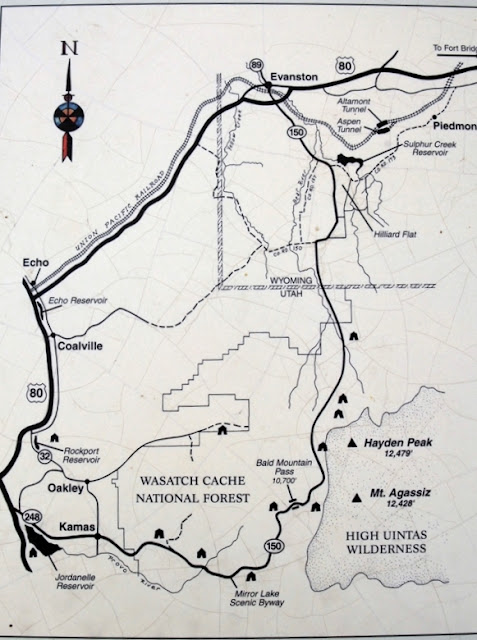

The route was up to the Mirror Lake Scenic Byway as seen in the Google Earth SPOT view of the trip.

I show a view of the highway with the DEER CAUTION sign for a purpose.

Even in the daytime one often sees deer along and crossing the route, and I recommend caution, driving below the speed limit. Especially is this important at night. I know what I’m talking about as a few years ago I was returning from a backpack at night, and I swear I was driving carefully, but nonetheless a deer RAN INTO ME! I had to wait for a Highway Patrolman, and then a wrecker. A black moose is even harder to see and could wipe you out, so be careful and enjoy yourself more.

Cut timber can be seen along the highway, as this is a multi-use Forest used for forest products, hunting, fishing, grazing, and in some areas even oil and natural gas production–as I’ll mention in a moment.

We have now climbed and left behind us Bald Mt. Pass, and look eastward with Rocky Sea Pass on the left, and Cyclone Pass on the right, both accessed by the wonderful Highline Trail.

Drive carefully and enjoy the beauties all around you. We are now heading down to the north.

Here we pass the road to Christmas Meadows and continue north.

Nearby our sheepherder friends were camped seen the week before driving their herd from Wyoming towards the High Uintas.

Then up the highway I stopped at the Bear River Ranger Station to learn what I could. It’s more than worth your while to stop–with clean restrooms, and cold water.

You can get all kinds of information, maps, books, postcards, etc.

And out back there is a real tie hack cabin with pictorial displays that explain all about these “unsung American heroes.”

Then on to the BEAR RIVER RESORT.

ATV rentals (snowmobiles in winter) and cabins for rent with satellite TV.

THE BEAR RIVER is all over this trip report. Remember this is one unique river beginning in the Uintas, flowing north into Wyoming, then swinging west into Idaho where it turns south flowing back into Utah and into the Great Salt Lake, its 500 mile course making it the largest river in North America that doesn’t empty into an ocean.

The Bear River was named in 1818 by Michele Bourdon, a 21 year old French-Canadian trapper for the Hudson Bay Fur Co. He was impressed by many bears in the area. In 1819 along the river he named he was killed by Indians.

Now on to Wyoming to search for the location of “The liveliest city, if not the wickedest in America,” (1868) BEARTOWN.

Additional reports on the ghost towns of Hilliard and Piedmont, Wyoming were originally next in this report, but will now be found after the report on the Howe Feeder Flume.

Next up THE SEARCH FOR BEARTOWN:

Part of that search included in 2009 a visit to the Public Library in Mt. View, Wyoming

and from there I made contacts with the library in Evanston. In Mt. View I photographed the following page about Bear Town.

Our search for Bear Town takes us past Sulphur Reservoir. Bear Town’s location will be in the distance down below the dam.

We are now back on the highway, at the 2nd tourist stop where historical signs tell us the story.

Below is apparently the only photograph of this short-lived frontier town that just in a year or so grew to 2,000 people with general stores, boarding houses, livery stable, saloons, gambling halls and a traveling newspaper, The Frontier Index. My first objective was to find its location. Next I had said that I didn’t believe that “Nothing remains,” so I had to find something, even if it was just an old piece of wood. How could I ever have hoped for even finding the culprit for having “whipped” the crowd into such a lawless “frenzy” that it turned into the “bloodiest battle between whites in the history of Wyoming?”

I searched for the area that would match the hills behind the town’s photo and added below my photo of the spot that seemed to be a quite accurate match.

In my research I learned that an ex-lawman, Tom Smith, came to Bear Town working as a teamster, but soon became the marshal. He had been a professional boxer and was famous for often being un-armed and subduing criminals with his fists. He did his darndest to keep the vigilantes and the criminals from fighting it out, but failed. From there on he was known as Tom “Bear River” Smith and went on to become the marshal of Abilene, Kansas where he was killed in action by outlaws. My complete writing will give many interesting details about his life.

Marshal Tom “Bear River” Smith

There are several versions of what happened in Bear Town, and I will include all of them in my final writing, but the stories go from one survivor of the battle saying there were 53 dead–all but one bad guys, to the controversial journalist Legh R Freeman, who had been the catalyst in the fight, saying 40 bad guys were buried around where the criminals had burned down his printing establishment. Historians feel that the total dead count was more like 17-18. The vigilantes had hung 3 of the rowdies who they were sure were involved in murders. The bad guys then got organized and came for the honorable citizens who had holed up in a store. When the bad guys approached 15 of them were instantly cut down by furious fire from new Henry Rifles in the hands of the good guys. Freeman is the one who dubbed Bear Town as “the liveliest city, if not the wickedest in America.”

That turned out to be the bloodiest battle between whites in the history of Wyoming. With that the Union Pacific Railroad decided not to run a spur to the town from the main line, and the town died. It disappeared, supposedly with nothing remaining.

I drove and hiked around the area searching for something that might be “remnants” of the town. I talked to a rancher who pointed to the area below as a spot behind the house where the Cavalry would camp out, and where he has found old mule shoes.

He joked about the fabled $50,000 in gold buried in the area. I asked if he had found it, and got a toothless grin and “Even if I had I wouldn’t be telling you!”

In my explorations I went for outlying areas that would have been garbage dumps and found a few items, mainly some “old pieces of wood” seen below.

Then I stumbled upon the important find. I have found in my research that usually the “tie hackers” and railroad workers were heavy drinkers. Of course the criminal element that were attracted to these frontier towns, especially to the saloons, gambling halls, and brothels, were also heavy drinkers. So is what I found hard evidence of this and the culprit in the whole history?

WOW! Didn’t know it had been around that long.

So we say goodby to BEAR TOWN for the present, or should we say, THE GHOST OF BEAR TOWN, looking over the spot where it had been with the High Uintas in the far distance to the south.

In this extremely brief summary of Beartown, I have only given you a few tidbits of the fascinating and incredibly action filled history, but eventually I’ll get the whole story told, including a number of accounts from journals and dairies of that period. We might just get it told in a big way deserving of this true and crucial chapter of our Western history.

THE HILLIARD FLUME

Now lets get back to the High Untas and do some exploring.

From 1873 to 1880 the Hilliard Flume and Lumber Co. provided railroad ties, mine props, cord wood, etc. to the railroad, and others users. As we have seen in Hilliard, Wyoming a series of kilns were constructed, as also in Piedmont a bit further to the east, where cord wood was turned into charcoal for the railroad, and iron smelters in Utah and elsewhere. A 36 mile long wood flume was constructed to Hilliard from the Gold Hill area of the Uintas west of the present Mirror Lake Byway.

The flume was V shaped about 36″ x 36″ built with heavy 3″x12″ planks. As it went down the mountain, it at times went through cuts dug through the rocky terrain, and at times was held up by a trestle one report says 16 feet high, and another states it being 30 feet high at Hilliard where the train passed underneath the flume.

80 tons of square iron nails or spikes, like you see above, were used in the construction that in the beginning was known as “Sloan’s Folly,” but it was successful for 7 years and perhaps more and became known as “an engineering marvel.” The water would move the wood products along about 15 miles per hour, making it to Hilliard in about 2 hours. The nails were found on my second exploratory trip when I got the first photographs of remnants of the flume I know of. The longest nails are 6 inches long.

THE HOWE FEEDER FLUME

To add more lumber products, and to keep the water flow up another flume was constructed to the east along Main Fork (of Stillwater Fk of Bear River), a stream that originates in the Hell Hole Basin, and which joins Stillwater fork 2 miles downstream from the Christmas Meadows Trailhead. In 1873 this was a virgin timber area with good water flow so it was perfect for the needs of the Flume Co. It was called the Howe Feeder Flume. This was going to be my focus on this trip assuming access would be easy. How wrong I was!

Once down out of the mountains a bit in flatter country you come to a turn-off to the southeast that leads to Christmas Meadows.

Drive about a mile to the first turn-off to the west and go towards “Road Gated.”

You are now in “tie hacker” country, driving through beautiful lodge pole pine forests–their preferred trees.

I add the winter photo below as that is when they worked the most–under the most difficult conditions. They were tough “hombres” to say the least.

In my research I found it stated, “very scanty historical records in existence.” Especially is this true during the early period, from 1867 to 1880 before the Forest Service even existed. More records are available for the 2nd period from about 1912 to 1935. My guide for this early period was a 1978 study that itself said, “…structures are badly deteriorated.”

What might I find 32 years later?

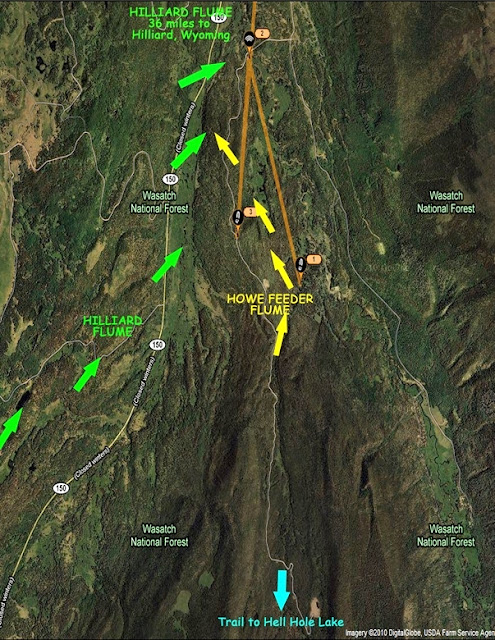

My first find was a locked gate on the very good road and bridge that crossed Stillwater Fork. Later at the Bear River Ranger Station I learned that the road had been constructed way up the canyon by an oil and natural gas company, but only to find they couldn’t exploit the area. Some maps show the road stopping at the bridge, with the Hell Hole Lake Trail continuing from there. Other maps show a jeep road going part of the way up the canyon. The Google Earth SPOT view I got after the trip follows and should be explained.

The green arrows on the left show the beginning and route of the Hilliard Flume coming down off of Gold Hill, crossing the highway (it isn’t marked where) and then joins the Howe Feeder Flume about 1 mile above where Stillwater Fork joins Hayden Fork to form the Bear River.

At the tail end of my last report (Trip #3) I mentioned the Hilliard Flume and a search I had made in 2009 but the road became very difficult for my small SUV and I turned back, but I did find a cut that had been made for the flume about where the 2nd green arrow is, and nearby the ruins of a tie hack cabin.

The yellow arrows more or less indicate the Howe Feeder starting along Main Fork and cutting across to finally joint the Hilliard Flume. The bridge and my camp were at #2. From there you see a straight orange line to #1. That is the distance I hiked the first day, about 2 miles in my attempt to find remnants of the feeder flume, but it was anything but a straight line–most of it tough bushwhacking through tangles of downed timber. I started up the road crossing the bridge, but was careful to watch for signs of what is called a “historical road” that would take off and angle towards the stream.

So off I went up the road, of course photographing the beauties along the way, like this Meadow Salsify, that is more a common foothills flowers, here found at about 9,000 ft. elevation.

I was hiking through lodge pole pine forests that were very thick.

All of a sudden I noticed on my left what looked like an old roadway and turned into it.

Often the “historical road” disappeared but usually by just going where it seemed right I would find it again.

The bushwhacking wasn’t that hard as I found plenty of reasons to go slow and stop often.

I was constantly scanning on both sides, up ahead, and even backwards attempting to notice any kind of structure that wasn’t natural and might be a remnant of the flume and/or the tie hackers.

This one certainly wasn’t natural, but who knows what? Then I found the roadway heading down towards the stream.

Nothing from our tie hacks, but no reason to get bored–rather inspired by the wonders of nature.

Then all of a sudden something that wasn’t natural.

This reminded me of piles of rotting logs I have found along the Middle Fork of Blacks Fork.

I finally made it to Main Fork, but what a tangle of downed timber. I tried my darndest to follow it upstream, and did keep track of the road for a while.

Along Main Fork here and there I would find remnants of the Historical Road.

Eventually the going became a real chore, and it was getting late, so I decided to backtrack to camp hoping to see something along the way I had missed. Back at home comparing my route to the study’s schematic of possible remnants superimposed on a topographical map, I could see I hadn’t gone far enough. I’ll show that topo map in a moment.

Wild Forget-me-nots.

All along the way I found many treasures, but no remnant of the flume. The next morning, not having this Google Earth view and knowing that the graded road went way up the canyon, I decided to walk the road at a quick pace for 1 hour which I did without finding anything.

Later at home I did what I should have done before this trip. I made a copy of the topographical map of the same area, then matched the contour lines with the 1978 study map and sketched in exactly where the flume had gone and where there were remnants back 32 years ago.

The crude purple with the heavy yellow line inside is basically where the Howe Feeder Flume went. My bushwhacking route following the Historical Road was the red dashed route a bit further north. As often happens when exploring one learns a lot, and ends up being better prepared to get the job done on the next adventure–which will be soon. I will begin the search near the Mirror Lake Scenic Byway where a jeep road crosses Hayden Fork and a trail begins heading for Hell Hole Lake. That trail apparently closely follows where the feeder flume came down, with sites along Main Fork paralleling the Hell Hole Trail. So I’m chomping at the bit to get up in the High Uintas again and return with a good report.

NOW LET’S SEARCH FOR THE HILLIARD and PIEDMONT GHOST TOWNS

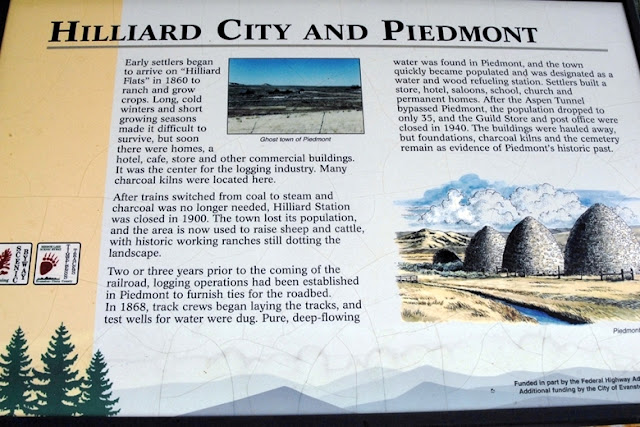

About 20 miles into Wyoming you come to this turn-off with important and interesting historical information of the area. I”ll attach here large views of all of them so those interested can read, and learn more about this fascinating area. Last of all I’ll get to our objective of several “tie hacker period ghosts.”

Here you see the Hilliard Flume coming down from the Uintas, held up by 30 foot high trestles and the 80 tons of square iron spikes.

We will now drive out past Sulphur Creek Reservoir to see what is left of Hilliard. As you see below it is now made up of ranches and homes.

I was able to detect some remains of a couple of the kilns mixed in with ranch buildings and machinery.

I’ll zoom in so you can see what I was seeing–ruins of a couple of kilns.

Below is the Google Earth view of the area. We’ll now travel eastward to the Piedmont Ghost town where the charcoal kilns are well preserved.

Below we are viewing from the left, the area of Beartown, then Hilliard, and Piedmont on the east or to the right. The Piedmont ghost town is to the right of the reservoir. To the far right you can just barely see 3 light dots–the kilns seen next.

Water was abundant in the area and a town grew. The settlers built a store, hotel, saloons, school, church and homes. It became a popular area for the soldiers from Ft. Bridger who would come for a bit of “Rest and Recreation.” When the railroad bypassed Piedmont the town gradually shrank, the last store and post office finally closed in 1940 turning it into a “Ghost town.”

This ghost town is connected to the “tie hackers” because they provided the wood that was turned into charcoal. Eventually coal mines in Wyoming and Utah made charcoal obsolete.

I made an exploratory trip into this area during the summer of 2009. You can see my more complete report on the area and many other tie hack sites I found on that trip. If interested go to: 2009 TIE HACK SEARCH. Said 2009 trips are in the Galleries section of this website. Soon I will pull all these exploratory trips and reports into one writing.

Except for the kilns and the cemetery, this is all private land with No Trespassing signs. I zoomed in from the road.

This is likely the school ruins.

Across the gully and stream we see the cemetery up on the hill.

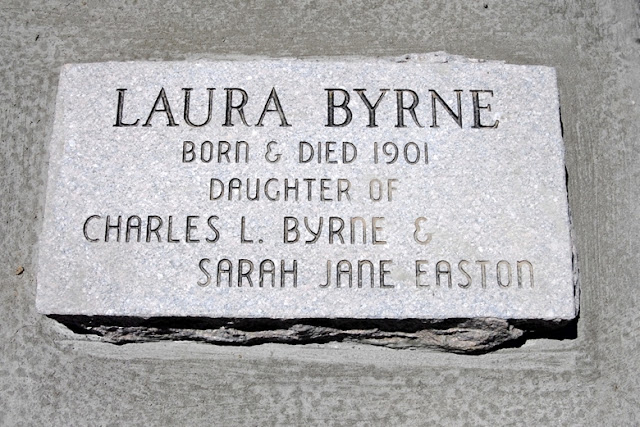

I photographed every tombstone and in my 2009 report give some interesting statistics that show how tough pioneer life was. In the final writing I will do on this pioneer period I will include all the photographs for anyone who wants to really understand. I’ll insert only one here from 1900 of a child born but died on that same day.

I decided to add one more, the last person buried in the cemetery — in 1998, indicating that the ties to this pioneer community still run deep among their descendants.

Before my final publication I will do a little investigation and find some of these descendants and add some real personal information.

I’ve got PIONEER DAY on my schedule for the 24th, then a trip to New Mexico for a grandson’s wedding reception, so in a couple of weeks I’ll be back on the Uinta Project. Most likely it will be with more exploring to find and photograph real remnants of the flumes and whatever explorations in the high country my work will permit. Tune in to KSL OUTDOORS RADIO and call in your questions or comments.

I welcome any questions or comments.

We are historic rail road fans, and along with Drake Hokanson’s “bible” from Trains Mag “Journey to Promontory”, we went to Piedmont, scene of Dr. Durant’s “detainment”, last year. Another area of artifact’, is the Dale Creek trestle site near Laramie, a place I intend to visit soon. Also, Echo City is rich in interpretive signs. And, of course, the original right of way from Promontory Summit, east to Lucin, is quite a memorable trip. Thanks, and comments welcome.

The trouble with all the history about the Transcontinental Railway is that the TIE HACKERS are never mentioned, nor given credit for what they did–without which there wouldn’t have been a Transcontinental Railroad. I have tried to remedy that a little in my BOOK.