A SEARCH THAT REQUIRED FIGHTING A BEAST….and it was bloody!

A few weeks ago half of my trip failed (see: Trip #3a). I did find the ghost of BEARTOWN which was BIG, but my search for remnants of the Howe Feeder Flume in the Bear River drainage failed. However, that led to better research and puting 2 + 2 together in readiness for this trip to find and photograph an important part of the Tie Hacker Culture. So I packed up for an overnight trip to get the first photographs that I know exist of said “remnants.”

If you haven’t learned about these “unsung American heroes” you can see my first report at:

You can also learn more from my 2009 report HOT ON THE TRAIL OF THE TIE HACKS and from my report this summer SEARCH FOR BEARTOWN

Now to the adventure of August 6-7 in the lodgepole pine belt of the High Uinta’s North Slope where in 1867 the sound of broad axes echoed off the mountains as

Irish tie hackers went to work to hew millions of railroad ties for the Transcontinental Railroad crossing Wyoming to the north. They also created mine props, and cord wood burned in kilns to produce charcoal.

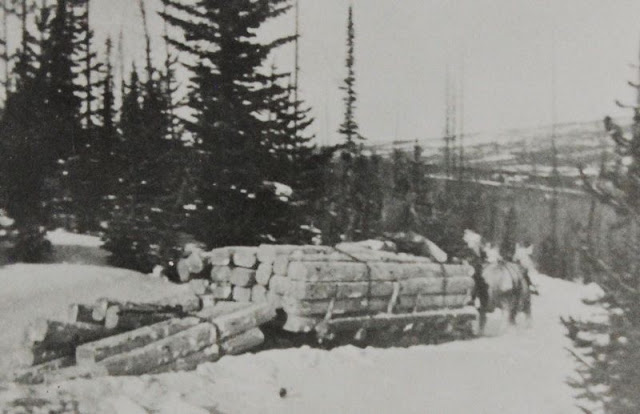

Much of the tie hacks work was done in the winter when transporting the ties in sleds was easier.

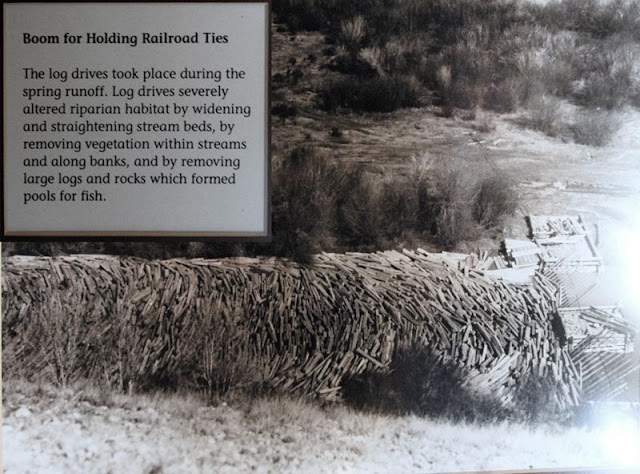

They were accumulated behind wood dams called “splash dams.” There they waited for the Spring runoff as you see below. When all was ready the dams were blown with dynamite and the flood was on carrying the ties down into Wyoming where they were picked up by the railroad. The tie hacks accompanied these drives to undo snags and blockages and keep the ties moving north. Some of you might be imagining that a lot of damage was done to the stream beds which did happen. Eventually better solutions were thought of, one of them being the theme of this article.

Remnants of some of their splash dams can be seen in several places. One of the best is on West Fork of Smith’s Fork as you see below. This is not a drainage visited very often by outdoorsmen.

Other than using the rivers to transport the timber products, the only other solution attempted was the HILLIARD FLUME as described below.

The flume was V shaped about 36″ x 36″ built with heavy 3″x12″ planks. As it went down the mountain, it at times went through cuts dug through the rocky terrain, and at times was held up by a trestle one report says 16 feet high, and another states it being 30 feet high at Hilliard where it was described as an “engineering marvel.” 80 tons of square iron spikes were used in the construction that in the beginning was known as “Sloan’s Folly,” but the engineering feat was successful for 7 years and perhaps more. The water would move the wood products along about 15 miles per hour, making it to Hilliard in about 2 hours.

Part of the system was what became known as THE HOWE FEEDER FLUME, a somewhat smaller flume, for example using only 2 inch thick planks, designed to help keep up the volume of water, and also bring wood products from a nearby virgin area–Main Fork of Stillwater Fork born in the alpine Hell Hole Basin on the north slope of A-1 Peak.

In my efforts to understand the tie hackers I acquired several reports such as you see below, in which the Howe Feeder Flume is described with diagrams indicating where the known elements in the system were found “badly deteriorated” in 1978. I wasn’t sure what I would find, if anything.

Since I failed in my first effort to find remnants of the Howe Flume I took a topographical view of the area and matched the contour lines to sketch in the study diagram and found that the “Historical Road” used by the tie hackers coincided with the trail that backpackers use to hike into the Hell Hole Drainage.

So on Friday, August 6th I headed for the High Uintas getting on the Mirror Lake Scenic Byway to get over Bald Pass and down to the target area.

As I traveled I saw lumbermen working on the southern portion of the Byway, and had go by me several trucks loaded with timber from our multiple-use Forest. The first stop is at the sign to Gold Hill.

Just for your information I’ll turn left onto the Gold Hill Road.

Gold Hill is the area where the HILLIARD FLUME begins. The 1978 literature says that nothing remains of the Flume, but there are ruins of buildings when there was a community of up to 500 people. I’ve found cuts up high as I showed in my last report, but still have to get to the ghost town. Let me warn you that this is a pretty tough road. To get up high it is best to go down the Byway a bit and go up the Whitney Reservoir road. I”ll turn around now and go back to the Byway. The sign will give you an idea where you’re at from Kamas, or Evanston.

My target area is just across the highway to the east where a short road ends at a parking spot for those heading for Hell Hole Lake. Some maps indicate that the trail is also a jeep road, and one of the popular High Uinta guide books says you can cross the stream, Hayden Fork, in your 4×4 and drive for about 1 mile, but believe me that isn’t possible anymore.

I parked a bit back in the aspens at a very convenient camping spot and then began my explorations. It looked like the weather might close in on me so I decided to do my darnedest to find remnants of the Hilliard Flume that came down from Gold Hill crossing the highway most likely a bit up from the turn-off and coming down the west side of Hayden’s Fork and a mile or so downstream to the north connect to the Howe Feeder.

Wouldn’t you know it, I was parked right in a cut where the Hilliard Flume continued north. Do you see the depression–that is man-made? I followed it north. In these photos we are looking back, south or what would have been upstream.

We continue north, looking back as we go.

As the cut came out into the flat it is disguised by a bunch of willows. Below we are looking back on this spot.

We now turn around and look north across sagebrush and willow flats. On these flats the flume was supported by wood trestles. The idea of course was to maintain the proper declination so the water would remain at a steady 15 miles per hour. The Howe Feeder Flume joined the Hilliard Flume about a mile north, coming in from the east or the right.

Below from this spot we look east towards the canyon of Stillwater Fork, but in the right center you see a dark ridge in shadow, then closer a lighted ridge. This line marks the Main Fork Canyon where the Howe flume originated coming down a unique gently slopping canyon about in the middle of this photo. That’s where we head next.

It is now the next day, Saturday. We have crossed Hayden Fork following the trail and old jeep road heading east. The first evidence I was looking for was a “cut” described as shallow and hard to recognize. This is possibly it.

As you hike you have to scan ahead, to both sides, and often should turn around and look where you came from, always trying to pinpoint any feature or structure that is not natural, but man-made. The first of such, for sure is seen below.

I got photographs from all sides and angles, but include this shot that gives the general idea. The experts state that this was likely a loading platform. They also state that the flume went directly over this log structure.

A bit further along I was surprised to find a warning sign.

I was on the lookout for another “cut.” Soon on my left up above the dry creek bed I detected the cut. Do you see it to the left of the boulders?

Here we are up above it, looking down on the trail and creek bed to the far left, the cut cutting across the center of the photo.

It might be a bit hard to recognize, but believe me we are seeing here a man-made cut with a gentle turn taking it down the canyon. Then I came gradually up out of the little side-canyon and crossed the road shown in my last report. It comes up from a gated bridge on Stillwater Fork. It is interesting to note that the small side-canyon we just came up starts right here and was a perfect place for the flume to go on down to the main flume. Turning around to look to the east we look down into the canyon of Main Fork.

Main Fork is not too far down from this point where the flume crossed and went west to Hayden Fork and the main flume. The construction of this road would have obliterated for some distance anything that might have been left of the flume. For some reason there is a chain link fence here stopping one from going down to the stream, but up the road 50 yards it ended and I was able to slide down a very short distance and was on the “Historic Road.”

What the study calls “The historic road” is very visible and easy to follow. I was now scanning both sides for signs of the flume, and camps the tie hackers had all along the stream.

Soon I noticed a side road heading down towards the stream and there found a log structure you see below. It was probably a structure that held up the flume, as we will see in a moment. Continuing up the canyon along the river was a very marshy area and so I backtracked to the historical road to continue up the canyon.

I was now looking for a camp area and further along there was a clear view from the road down towards the stream showing a dry rocky shelf paralleling the stream and I detected what might be the outline of a cabin ruin.

Down on the rocky shelf I immediately found the ruins of a cabin and took an overall view as seen below and then from all sides. There was mound in the middle with several relics in view that I’ll show in a moment. It seemed to likely be a pile of silted over garbage. Such garbage dumps are treasures for archeologist’s. I resisted the temptation of digging into it, and would only do so if prepared to do so carefully, mapping the finds, labeling them properly, etc.

Usually tie hack cabins from this early period (1867 to 1880) were very simple without windows, but had a fireplace the remnants of which are seen below.

Below is a photograph of a reconstructed tie hack cabin at the Mt. View Wyoming Forest Service Ranger Station. It was dismantled at the tie hack Steele Creek Commissary ruins near the Hewinta Guard Station on the West Fork of Smiths Fork. It is from the 1912-1935 tie hacker period with windows, and an iron stove inside, typical of the modern period. What we are seeing along Main Fork is very old and of course deteriorated.

From the surface of the garbage dump we see our first square nail common during that period, and a piece of glass with “Co” distinguishable, probably abbreviated for Company.

I continued down the shelf, this view looking back, finding other even more deteriorated ruins of cabins, and then got to the stream, Main Fork.

I began finding other rotted log structures, that in hindsight I conclude were part of the support structure for the flume.

Then I began finding brackets that would have been used to support the flume with large square iron nails holding them together. I had dreamed finding some of these nails, 80 tons of which were used to put the flumes together (the Hilliard and Howe). Eureka! My dream was fulfilled.

In the area I began finding plants and flowers I hadn’t seen before. This one was unique–I hope to find it blossoming one day soon.

I continued up the Historical Road and on cue it angled down to the stream where there had been a bridge–but with nothing remaining. As it rotted the pieces that would have been recognizable were probably washed downstream with spring runoffs. I was now looking for the “flume” as marked on the study map being on my side (west) of the stream.

Downed timber was everywhere making progress very difficult. In addition there was a wide area along the stream that was very swampy making moving up the stream almost impossible.

The abundant wildflowers were the only consolation for my tiring body.

Another new variety was part of the marsh. At the end of the summer season I will go through all the wildflower photographs from this summer adding all the new ones, and better photos of others. The total varieties in my two wildflower albums will more than likely surpass 245.

I zoomed in.

I had a ways to go before coming to the area marked “flume” so decided to get up out of the bog. I moved up into the lodgepole pines, but there the problem was downed timber. I was getting tired, my legs trembling a bit with fatigue as I stepped over branches and logs. Take note, that is a danger sign.

I should keep this event secret, but relate it here in the hope that a few will learn from my experiences, and maybe even save their lives–so, take note.

All of a sudden as I was stepping over a log I didn’t step high enough, caught my toe and went down like a rock face first. My camera was in my right hand–and I saved it, but not my face.

It reminded me of a time on my farm in Guatemala when I was approaching the cement stairs up to the laundry room door. I had a glass bottle of Orange Crush in one hand. My German Shepard guard dog, Goku, was happy to see me and jumped at me causing me to lose my balance and fall on the cement stairs. I adeptly saved my Orange Crush, but came down hard on my forehead creating a gash about 4 inches long that squirted blood everywhere–so off to the hospital to get sewed up.

Back to the High Uintas, I laid amidst sharp branches of the downed timber stunned. Blood was coming from wounds on my left arm, and both legs, but mainly from my left cheek just below my eye. Blood blurred my vision and I instantly wondered if my eye was gone. “Will this be my first need of hitting the 911 button of my SPOT TRACKER?” But, there would be a problem of them finding me. A helicopter would never see me in the thick timber. They would have to come in on foot with a GPS device to find my coordinates. This was my first trip since 2003 not having a satellite phone with me.

NOTE: I made a terrible blunder as a photographer. Before trying to stop the bleeding I should have grabbed my camera and taken the pictures. What you see here is after I got cleaned up and not very impressive.

I said a quick prayer for divine help, rolled over and pulled my red bandanna out of my pocket and put pressure on the wound under my eye. I realized my eye was alright, and thanked the Lord for my good fortune. Once the bleeding there seemed stopped I worked on the arm, mainly using the bandanna as a bandage. In my backpacking article I talk about the critical importance of a bandanna for emergencies such as this. My supply of tissue paper was used to continue with pressure on the eye wound.

“I’d better get out of here,” I thought. “But, I’m so close to finding the flume.” On the other hand, “No one would blame me for heading for civilization.” It was obvious that I was tired and emotionally spent. In fact I felt rotten. The “BEAST of discouragement, of quitting, of giving up” was trying to control my life and keep me from achieving my goal. Like my friend Josh did with the bear that was killing him, I reached back with all my strength and “gave him my best Rocky Balboa punch right in the kisser.” For details of this story go to JOSH

The BEAST of QUITTING was stunned and let me go. I got to my feet and continued up the canyon, finally working my way back down to the stream about where I calculated the flume was, and all of a sudden I saw something unnatural.

The BEAST of QUITTING was stunned and let me go. I got to my feet and continued up the canyon, finally working my way back down to the stream about where I calculated the flume was, and all of a sudden I saw something unnatural.

It wasn’t much. I persisted and then it became obvious–I HAD FOUND THE FLUME!

The triangular brackets seen downstream where in view along with the planks.

The planks finally ran out and there continued up the canyon a series of the log structures that had supported the flume–similar to those I had seen downstream.

Some would say that I had just found “old pieces of wood,” but for me I was seeing real evidence of an unknown aspect of our history realized by what I have called “unsung American heroes,” rather than just see artist’s sketches and paintings. & historical descriptions. I also was lucky enough to get photos of a few of the more than 1,280,000 square nails used to create the flumes. The longest seen below is 6 inches long, weighing nearly 2 oz. I seemed to be able to feel during this experience the spirit of these toughest of the tough.

Now I could relax for a moment, clean and disinfect my wounds and head for civilization. With water from Main Fork I wet my bandana and cleaned off most of the blood, and then disinfected my wounds with insect repellant–and took a few pictures. Now a bit rested I clicked off another few photographs of gorgeous new flowers seen along the way.

A couple of hours later back at the car I did a more thorough job using Hand Sanitizer to clean all areas, and then applied Neosporin antibiotic/pain relieving ointment. All of these items are always part of my backpacking equipment. As I do this report 60 hours after the event I can safely say that infection in the wounds has been avoided.

NOW FOR A RUNDOWN OF THE TRIP

Below is the SPOT Tracker Google Earth view of my explorations on this trip. From 15 to 18 is the route along Main Fork, from about #15.5 up to #16 being the camp, and the flume in #18. From #11 to #15 is the canyon the Howe Flume went down, which actually is a seeming aberration in the topography that made it possible for the flume to get down to Hayden Fork and the Hilliard Flume. From #10 to #7 is the cut for the Hilliard Flume shown in the beginning of this article.

Next is the topographical map showing the various flumes and the path of exploration. Hope you can make heads or tails from it.

Remember that the flume came down out of the Uintas crossing into Wyoming and ending at Hilliard Flat where there were a whole bunch of kilns for making charcoal. Cord wood was also transported east to Piedmont where more kilns produced charcoal. The railroad track had gone through Piedmont and then to Hilliard, but the Aspen and Altamont Tunnels changed the course of the railroad from these two frontier towns, eventually turning them into Ghost towns.

Here you see the Hilliard Flume, 30 feet high arriving at Hilliard and the kilns.

Hilliard today is made up of ranches you see below.

The ruins of a kiln at Hilliard.

The town of Piedmont also used cord wood transported by water down the Hilliard Flume.

Three kilns in excellent condition are found at the Piedmont Ghost town.

Piedmont was a thriving town in the 1800’s where soldiers from Ft. Bridger would come for a weekend of fun. In large part it was dependant on the cord wood supplied by the tie hackers and transported down the Hilliard Flume.

The cemetery on the hill to the east of the road, along with the kilns, is the only portion of the ghost town accessible to the public.

From around 1860 on the ABC’s were taught in the Piedmont School. Hopefully one day our children and grandchildren in their schools will even be able to learn about our “unsung American tie hacker heroes.”

A WORD OR TWO OF CAUTION

First, when you are hiking, especially doing dangerous actions like high stepping through downed timber, or boulder hopping, when you feel tired enough to have legs tremble, STOP & REST. When fatigued you are in much greater danger of making a misstep, such as happened to me.

First, when you are hiking, especially doing dangerous actions like high stepping through downed timber, or boulder hopping, when you feel tired enough to have legs tremble, STOP & REST. When fatigued you are in much greater danger of making a misstep, such as happened to me.

Second, especially when alone always have at least a SPOT TRACKER as seen below.

And, if possible, a satellite phone–which I didn’t have on this Howe Feeder Flume trip, but will for my next into the West Beaver Creek Drainage in the northeastern High Uintas Wilderness.

For more on 7 distinct Survival experiences that just could save your life, go to SURVIVAL

Fascinating reading. Thanks for sharing your adventures Cordell!